The owl of Minerva spreads its wings only with the falling of the dusk. -Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel.

Following is the introduction to the Artist’s Talk I gave about this body of work on November 14, 2019.

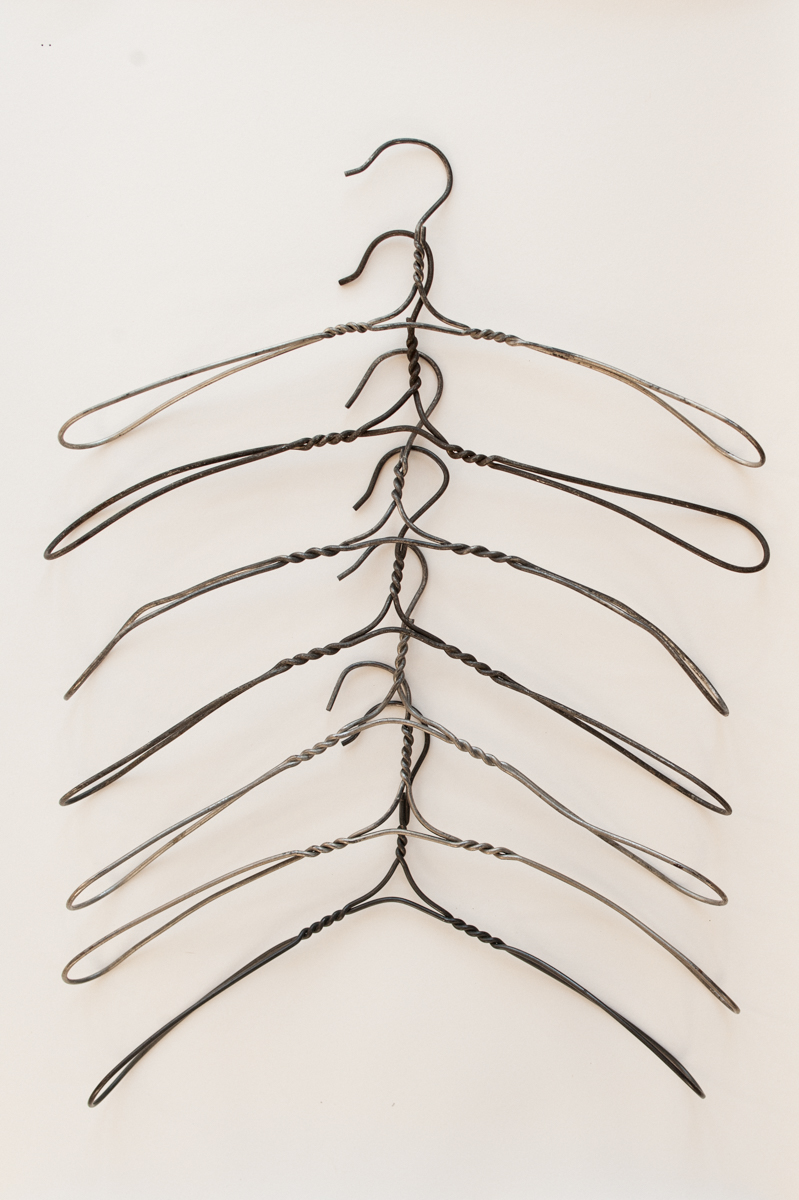

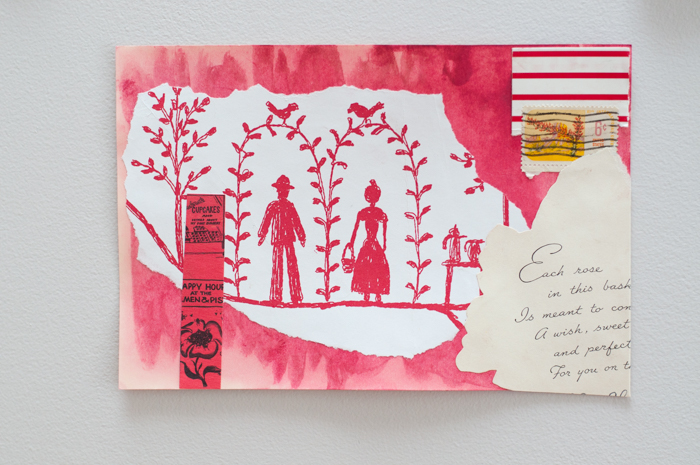

A few months back when I came in to talk to gallery owners Ross Martens and Darren O’berto about what my upcoming show was about, I couldn’t quite articulate my intentions. There were too many layers, too many stories crossing over themselves, diving down and gasping for breath. My last project, Voices of Resistance, had a message to shout, clear, and layered with history. This show for me is much more of an emotional journey of being, a collection of whispers and side stories, it is indirect and circuitous, but suffused with a sense of the glory of being, a sense of connection to creatures great and small and stories past, present and future. It is a quieter meditation, a search for an internal stillness amidst the chaos. I was recently listening to Oprah interview Pema Chodron and I was intrigued to hear of Chodron’s 100 day silent retreats, a turning inwards, a quieting, but in this quieting she talks about how we are all always putting energy out into the world, carving and shaping pathways by what we extend and this felt interesting to me, this idea of our impact in the very act of being. For me, stillness and quiet are essential, but they alone are not enough. I have a need to gather threads and find intrinsic similarities, spaces of resonance with strangers, with birds, with trees. This feels important, our intertwining. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

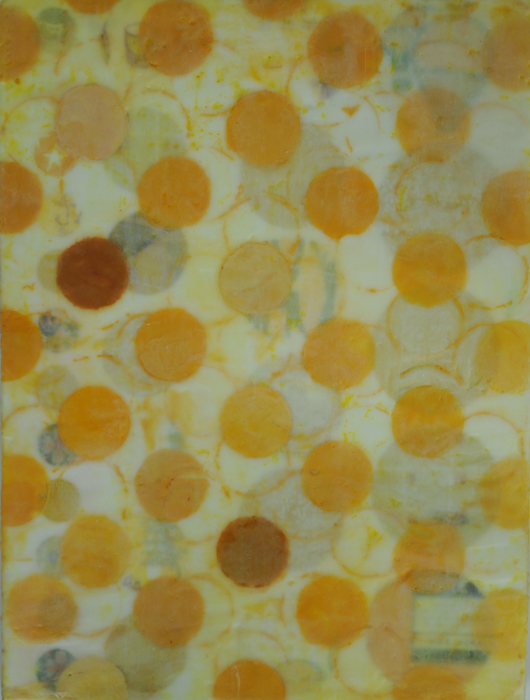

So a few foundational stories, I was in Alley Gallery a few years back talking to Ross about an idea for a Still Life, the theme Yellow, Bees and colony collapse. Ross offered that he had a goldfinch in his freezer that once he had intended to taxidermy, but that had not come to pass and if I might like it, it was mine to use. And so the Still Life, Goldfinch and the Colony that Collapsed came to be. Then I saw Darren’s incredible cyanotype with a gathering of bird bodies flecking the surface. I wondered at where he had found so many birds and learned of Allison Sloan’s project collecting birds that collided with newly built Northwestern University surfaces, a consequence of our development that does not take into consideration so many things about the natural world including flight patterns and visibility or how the bird’s eye sees. Many of Allison’s gathered birds are in these images. Over the years birds and flight have become, unconsciously, recurring themes for me and ones that have connected me to others. If you asked me what super power I’d like to have flight or invisibility, I would always choose flight. My grandparents were avid birders and so as a child, an attention to birds was paid. Growing up in New York City it was mainly pigeons with their purple-blue iridescent wings, shimmers of green, the rats of the bird world that captivated me, but it was my grandparents sharing with us their hours of footage of nesting Piping Plovers on remote and desolate beaches where they would spend their summers scoping the shift of bird populations and gathering shells, turning their footage into documentaries that struck and stuck somehow. And I guess I’ve always had a fascination with the murmurations of starlings, how they flock and fly and flip in these formations each of them a part of the whole. When 1 bird shifts, they all do. There is a sort of group think, a collective body. Then there is the hummingbird, in many ways the opposite of the starling, migrating 500 miles in a solo flight, intensely territorial. I think there is something in bird behavior that might reflect our own or better yet might teach us something about ourselves.

In some ways I imagine this body of work as a love letter to the planet, there are threads of story, an emotional bonding, a certain intensity between a girl and a bird, a girl and a flock of birds, another bird, another bird—each one she cherishes, each one she wants to catch and hold, unlocking the songs they have sung, the life that fluttered, the birds changing as she does. In this time of increasingly radical climate events, January temperatures in November, drifting arctic winds settling upon us climate anxiety, our unpredictable future, is elevated world-wide as we have begun to see climate refugees such as the Biloxi Chitimacha Choctaw of Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana, and the forced relocation of this tribe because of human caused climate change, uprooting them from their land, heritage and history, shifting the stories of future generations in the loss of familiar land because the sea is claiming this land as its own. And there are the rampant fires in California and Australia, whole towns engulfed and consumed like Paradise, floods and droughts destroying crops, I could go on, but I’ll leave that to the Naomi Klein’s of the world. In this time of climate anxiety, our hope feels essential. Our ability to find wonder in the magical world where narwhals and rhinoceros and morpho butterflies exist, where we as humans exist in so many different forms and yet despite our extreme differences we are still able to find mirrors and bridges in those around us. This our ability to have reverence for the life that has been lived and hope for the life that will be lived, that feels essential. As John Muir insists, “when we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.” And in this coupling with the universe, perhaps we are a little uncoupled from our ego based selves, allowed to open to something greater, something beyond us, a sense of deep time. Maybe that’s what this is about, connecting to that sense of deep time finding the reflections that reverberate and recur. Yonis Salk asked, “Are we being good ancestors?” And this is the question as we gaze so deep into the depths of past and future being, all the astonishing glory of this here comes with immense responsibility, the resonate impact of our being, of our legacy, I look at what we have inherited, what has been brought forward and what has been lost, for good and bad and I want to name it for the purposes of remembering beyond our botanies of destruction and excavate it for the purposes of understanding all the links the stitch time together.

And so this is what I came up with. I think the best way to go about sharing this all with you, or at least a little bit of my inner-workings, is to start from what I think of as the beginning. I’ll go around the room and speak about each piece, share with you a bit of backstory and read some of the poems tucked into these envelopes, then if there are any questions or comments we can talk more… And then I talked and people asked questions and a sort of unfolding release occurred.

Unfortunately this talk was not recorded, but if you have any specific questions about a piece in the show please feel free to ask. The full body of work, minus the 14 accompanying poems, can be seen here.

In the meantime Eco-Parent Magazine has just published a feature article in their Winter 2019 issue on The Alchemy of Hope by Manda Aufoches Gillespie. This article includes a bit about my bird collecting and is accompanied by images from Possibility of Multitudes. The magazine will hit newstands in the US and Canada on December 5th, following is the language of the article:

THE ALCHEMY OF HOPE

In the Era of Loneliness

by manda aufochs gillespie

“The dark is rising,” I say to my friend, Vanessa, a photographer who has called to tell me how a bird fell out of the sky and landed at her feet, dead, during her morning walk. She is obsessed with birds. She has hundreds of them in her freezer. Songbirds collected and given a second life captured in chilling, beautiful tableaus where they appear piled and presented like a cake, falling lifeless around the figure of a woman, or held in hand, the colours persistent, their forms perfect, even in death. “The birds are dying. They will continue to die. Like the canaries in the mines,” my friend says.

As I write this the CBC is on in the background reporting on the “overlooked biodiversity crisis” represent by the 2.9 billion birds lost in North America alone over the last 50 years. When miners took canaries into the coal mines with them, the birds were to act as warning indicators: the presence of methane or carbon monoxide levels rising would kill the canaries giving the miners enough time to escape before they too succumbed to the toxic air. Here we are, watching the birds die, a warning of things to come, and yet we can’t seem to find our way out.

TWELVE MINUTES BEFORE MIDNIGHT

We live in what geologists are calling the Anthropocene epoch, anthropo meaning “human” and cene meaning “new or recent”. And as humans, we’ve been granted the role of chief architect of this new epoch, yet we are just a blip, a singular event in the grand scale of time. The earth is around 4.6 billion years old, and humans a mere 200,000. To put it into perspective, if we were to squeeze the history of the earth into one calendar year, with earth being formed on January 1, the first life—algae—didn’t appear until March and the first fish didn’t appear until November. Dinosaurs appeared for ten days around Christmas, and Homo sapiens showed up 12 minutes before midnight on New Year’s Eve.

Human’s may have arrived late to the party, but we have not arrived quietly. Instead, we have been responsible for atrocities, mass extinctions, and deforestation that arguably mark the end of the 12,000 year Holocene—an age characterized by climate stability and the rise of civilization—and usher in the Anthropocene (literally meaning “the age of humans”). The Anthropocene has not yet been dated with unanimity because to be defined as an epoch in geologic terms the remnants of the era must be literally set in stone and observable across the entire planet. Candidates to mark this advent cluster around 1945 (the date of the first detonation of a nuclear device), and include the radioactive signatures left by the atom bomb, permanent traces of lead from gasoline and its byproducts, and one day, could also include our fossilized remains that will bear the unique carbon isotopes of burning fossil fuels.

Yes, we have ignored those canaries and have invited the sixth great extinction into the earth’s history. The natural rate of extinction has been one to five species per year. Our reality, however, is the epic daily loss of dozens of species—99 percent of which is caused by human influence as a result of habitat loss, climate destabilization, and toxic pollution. Scientists estimate that 50 percent of all the species we once shared the planet with may be extinct by mid-century. Nearly every single bird that hits the forest floor or the sidewalk at our feet: our fault.

THE AGE OF LONELINESS

Vanessa refers to our era as the Eremocine—The Age of Loneliness—a term coined by environmental hero and two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning biologist, E.O. Wilson, who envisions an earth that will have little left other than humans and domesticated plants and animals along with fungi, microbes, and jellyfish. I think about the eerie landscapes of Vanessa’s photos: places not quite real, but nevertheless familiar. Places often haunting in their loneliness. Will we miss—truly miss in our deepest souls—the birds and beasts and flora we never really knew? Wilson says we will, and indeed, already do. The International Psychoanalytical Association recognizes climate change as “the biggest global health threat of the 21st century,” with nature deficit disorder, climate grief, and eco-anxiety becoming realities for many people.

I have a sense that as a people we’ve forgotten something essential to survival. Maybe it boils down to not knowing how to live with this irony: to thrive knowing we will not survive, to live life even when its losses shatter us. How will we know ourselves and the deep, dark, unfathomable spaces without the otherness of the natural world? A world without wildness is a world without nature writers, without the E.O. Wilsons, Mary Olivers, Annie Dillards, and Wendell Berrys. Gone will be the guides to show us the deepest longings of our souls by taking us for a walk through an ant kingdom, into Blackwater Woods, along Tinker Creek, or onto a cherished Kentucky farm. Where will we go to learn to reach into those dark places inside and feel the glory of the light streaming in?

A friend recently came for dinner. She texted me in advance: “I can’t talk about climate change. I just spent two weeks uncontrollably crying.” She’d been reading Jem Bendell. A quick synopsis of the 36-page paper by the prominent academic basically amounts to this: It's too late to stop global warming. The apocalyptic times are already upon us. Even the privileged sitting in expensive homes in North America with plenty of food and water will be feeling the pain and experiencing the loss of societal collapse within the next ten years. “How do we parent through this?” is what my friend both wanted—and didn’t want—to discuss that night at dinner.

Rex Weyler, parent, author, and co-founder of Greenpeace, agrees that the human population has significantly overshot the threshold by which the earth can sustain us. “A year ago, I polled two dozen of the most advanced, educated, active, working ecologists and scientists I knew and asked them: What do you estimate would be a sustainable human population?” He included caveats: people had to still be able to live reasonably comfortable lives, eat good food every day, have access to some transport options, and wild ecosystems had to increase, not continue to shrink. The answers were estimates that ranged from 50 million to 2 billion.

In this lies the crux: will we, or will we not, live to see the sixth great extinction grow to include humans? Some say that we can still stop it if we reduce our greenhouse gasses, and consciously shrink human consumption and our populations quickly and dramatically. And there are others, like Jem Bendell, who suggest it is already underway. And while we may be able to lessen the impact, we must prepare for this extinction to personally and dramatically affect all human populations. To prepare, he says, means to identify the truly essential norms and behaviours we wish to preserve and work like hell to protect them as we prepare to relinquish all else.

AN EDUCATION IN REBELLION

This year, I took the train across Canada with my children and met Vanessa and hers in Montreal where we took part in an Extinction Rebellion event. “XR,” as it’s referred to, is a movement that uses civil disobedience and nonviolent resistance to protest climate breakdown, biodiversity loss, and the risks of social and ecological collapse. The activists performed a staged reenactment of the five previous extinctions in front of a very packed queue of ticketholders waiting to get into the Grand Prix. The reenactment portrayed the extinctions as groups of people running a slow-motion race, from the very beginning, to dinosaurs, and finally to humans. When they reached the point in the race that represented the current day, they all fell down as if dead. A group that included my children then ran up and outlined all the bodies in chalk while the rest of us chanted, “Extinc-tion Rebel-lion…Extinc-tion Rebel-lion.” The activists rose from the dead and the earnest troupe of perhaps a hundred stood incongruently facing thousands of car racing enthusiasts. Afterwards, the kids pulled out a pack of candy cigarettes they had been saving for a special occasion and pretended to smoke. The irony of it made me want to laugh and cry. None of us gets out alive.

BUT HOPE FLOATS

There is an alchemy that must happen in this place of uncertainty that is not unlike the alchemy that happens when one strives to consciously parent: the belief that our intentions can transform matter. If we can't save the world, perhaps with a little effort we can save ourselves and with an extra touch of magic, we can save our children.

Environmentalist Karen Mahon, founder of Climate Hope, got married this year. She also became an ordained monk. Mahon is intimately aware of just how vulnerable the human species is to joining the sixth great extinction and yet she still studied for ordination, and still chose to marry—for the first time, despite their kids being fully grown— and invite her entire community to join in the celebration. The monk who presided over the ceremony said it was an act of glorification: to reveal the glory of the heavens through our actions on earth. I can’t get enough of this idea of glorification. That we may believe in the power and the magic of a perfect day, of 11 homemade wedding cakes and 200 hand-made blintzes, and the significance of committing to another, not out of legal or social obligation but because it represents profound hope. Not ironically then, it would only make sense that Mahon’s organization defines hope as the refusal to give up on love.

NEVERTHELESS, SHE PERSISTED

Perhaps it is glorification at play as my friend collects hundreds of beautiful dead birds and gives them a second life in her art. Perhaps it is hope that allowed me to choose to have children despite what I knew about environmental toxins and their impacts on their small, developing bodies. Did my friends reverence of the fallen birds save even one live bird from death? Or did my knowledge save my children from the impact of toxins, keep their brains whole and unblemished, or make me a perfect parent-protector? It did not. My mistakes are many. I have fed my kids chemical-laden foods in a pinch, I did not wash the stinky chemicals off the new sheets I wrapped my newborn in, and I was chastised at my child’s fifth birthday party for feeding the whole gang a non-organic ice cream cake dyed the brightest, coal-tar-and-benzene-assisted-blue imaginable. Furthermore, my climate impact has not been the minimal impact of my friends in Guatemala where my children and I once lived for a short time. We fly, we drive a gas-guzzler, and we heat with wood.

What if the great destructive forces of the world, whatever one may believe them to be—capitalism, overpopulation, climate collapse—had been set into motion hundreds, or even thousands, of years before I chose whether to fly on that airplane or eat that non-pasture-raised hamburger or whether to have one child or two? For millennia we have alternately brutally destroyed and then ingeniously rebuilt the world more than once: World Wars, numerous genocides, the Spanish Flu, the Black Death, and Small Pox. We have had the Dark Ages, the Renaissance, and the Industrial Revolution. The world—or at least our time in it—is going to end, again, one day.

And I will keep choosing the hard act of getting up in the dark to have time to write these few words before sneaking out to the chicken coop to gather eggs to make breakfast. I’ll do it so there is time to walk the kilometre down and up, and up some more to meet the school bus, then back down and up to homeschool the other child, and squeeze in time to arrange a semester of speakers for a community organization I started. Hopefully in there I will get a chance to call my friend with her pile of dead birds that she has gathered to make art to remind us that despite it all there are so many moments of beauty, of connection, of light to experience while we are here. And when I call her I will tell her, “The light called the dark,” because I may not know how things will end this time, but what I do know is that because we are human, we will fail. Yet every time we fail, we get to choose to get up and try again, and that’s what it means to choose hope.

Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice.

From what I’ve tasted of desire

I hold with those who favor fire.

But if it had to perish twice,

I think I know enough of hate

To say that for destruction ice

Is also great

And would suffice.

--Fire and Ice by Robert Frost